- Home

- Jordan Ifueko

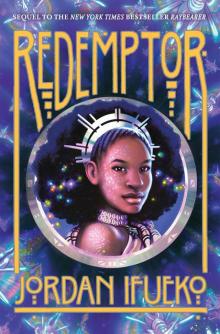

Redemptor Page 9

Redemptor Read online

Page 9

Why should you celebrate? The ghosts had hissed. Why should you live happy when we are dead? Do more—do more—pay for our lives.

“I’m not sure,” I said at last. “Not exactly. All I know is, before the visons appear . . . I almost feel like I’m enough. Like I’m doing the best I can, and I deserve to be Raybearer. Deserve to be empress. Then the voices make me feel . . . useless. Like there’s so much evil, so much injustice, and I have to fix it.”

“This is strange,” Emeronya said, peering again into her scrying glass. “I have heard of Underworld apparitions before, but—”

“Do you think they’re shades?” I asked hopefully. At least if the apparitions were real spirits, it would mean I was not going mad.

“Not exactly,” she said slowly. “Shades are souls that died recently. They visit our world only when summoned, and sometimes not even then. Afterward, they join Egungun’s Parade, traveling to their final resting place at Core. Some shades never make it to paradise, though. They just . . . linger in the Underworld. Unable to find rest. And sometimes—” She paused. “It’s said that abiku consume lost souls. Defile, reshape them until what’s left are creatures between death and resurrection. Beings that can appear as both spirit and flesh, known for mixing lies with the truth. Tar . . . you’re being haunted by ojiji.”

“It can’t be ojiji,” Kirah objected, as shivers chased up my glyph-covered arms. “Those are bully spirits—they coerce people into doing evil. To destroy themselves and others. They don’t coax people to solve injustice.”

“Maybe they’re taunting me,” I whispered. “Maybe they know that no matter how much I care, no matter how hard I try . . . it’ll never be enough.”

My voice broke. As hot tears sprang to my eyes, invisible caresses warmed my skin. Immediately, all eleven of my council siblings had bathed me with the Ray, expressing a depth of love that words never could. I closed my eyes, caressing them back—each member of my forever family, each branch of my external heartbeat.

Ours, they sang in wordless harmony. Tar is ours, and Tar is enough. And right when my shoulders began to relax . . .

It happened again.

A translucent Redemptor child shimmered into being, gliding across the salon floor and passing through the bodies of my siblings. The glyphs on my arms smoldered. The creature smiled emptily, holding a grimy finger to its lips.

The ojiji’s mouth did not move. Still, it said: Don’t tell them.

“It’s happening now, isn’t it?” demanded Kirah. She felt my forehead, her hazel eyes sharp and grave. “Tell me, and I’ll sing for you.”

Your friends do not see what you see, the apparition sighed. They are spoiled by privilege. Numb to the true cost of change.

I recoiled at the words, which rang true. I had just been thinking the same thing earlier, when Mayazatyl had whined about my desire to improve the empire. But Emeronya had said these creatures meant me harm. That they told both truth and lies.

They are blind, great Empress Redemptor. They are blind, and you are alone.

What was truth, and what was a lie?

My eyes slid to Kirah. I knew then, with grim intuition, that I did not have an illness my friends could cure. Kirah could sing down the moon and stars, and my siblings could cover me in hugs and spells and promises . . . and that undead child would still be there, lisping its cold, pure truth.

You are alone.

Woodenly, I pressed Kirah’s hand. From a distance, I heard my voice say, “Go on, all of you. I was overreacting. Do the jobs you’ve been training for. You’re right—I’ve been different. But now, I’ll be fine.” A smile stretched on my face as my stomach sank, sour with the certainty that this lie would be the first of many. “I’ll be just fine.”

CHAPTER 10

Eight of my eleven council siblings vanished toward the corners of the continent, and within hours, I stood with Dayo before the craggy Olojari Mountains, clutching my stomach from the lodestone journey.

“I wonder why that never gets easier,” Dayo mused as we left the guarded port.

I laughed shortly and stuck a finger in my ear, which still rang with enchanted vibrations. Thankfully, the ojiji appeared not to have followed me through the lodestone. Still, I wondered if they lay in wait, always just beyond human sight. Sweat beaded on my brow, and not just from fear. In contrast to Oluwan City with its cool coastal breezes, the Oluwani province of Olojari was several miles inland, with hot, dry air that tasted of soot.

“Getting dissolved, transported seventy miles, and slapped back together isn’t a skill you can practice,” I pointed out.

“Well, you’d be the expert,” Dayo said cheerily. “After twenty-six lodestones in a row. Maybe you’ll get immune.”

“I nearly died,” I reminded him. “I think I did die, for a minute. That part’s still a bit hazy. What I do remember involved a lot of puke.”

“Don’t say ‘puke,’ ” Dayo begged, then rifled through his gold-trimmed trousers to produce a vial of amber liquid. After tossing some back, he offered it to me. “New from Thérèse.”

The potion tasted strongly of ginger and burned as it went down, but did wonders to settle my stomach. I looked guiltily at the empty bottle, wishing I’d thought to share with our Imperial Guard escort. Sanjeet had stayed back to secure the capital and had sent a cohort of trusted warriors in his place. They followed a respectful distance behind as we neared the holy forge, trying their best not to look queasy.

The Holy Olojari Forge and iron quarry rested in the heart of a scruff-covered mountain, hollowed out over centuries for the purpose. As the temple prospered, a chain of villages had sprouted up at the mountain’s feet, servicing the forge with generations of miners, blacksmiths, and inns for the year-round influx of Ember-sect tourists.

At first, we passed through a patchwork of sumptuous noble villa estates, roofs dotted with iron statues of bluebloods—the same nobles, I imagined, who had managed the quarry on my ancestors’ behalf for generations. Every now and then, an orange fleck buzzed near my ear, and something sharp and piercingly hot accosted me in the face. Once, I slapped my neck and brought my hand away to reveal the squashed carcass of a tiny winged creature.

“Ina sprites,” Dayo observed. “Fire spirits. With so many, the forge must be thriving.”

But the closer we got to the temple, the more I sensed something terribly, terribly wrong. The villages, while numerous, were little more than tenements and mudhouses crowded together, with the occasional tourist’s inn surrounded by beggars. As far as I knew, the forge had employed Olojari commoners for hundreds of years. So why did so many live in squalor?

The narrow streets and markets lay spookily bare.

“Where is everyone?” I asked Dayo, careful to keep my voice low. “Do you think word got out about Umansa’s prophecy?”

“I don’t know,” Dayo replied. “But that’s not a good sign, is it?”

He pointed to a plume of smoke slowly filling the horizon. The mountain appeared to be steaming—unearthly tendrils of red, gold, and black rising from craggy rock.

We soon discovered where most of the villagers had gone. A crowd of thin, soot-covered commoners blocked access to the forge. Armed priests guarded the forge entrance: a tall, wide arch carved into the face of the mountain. Twin statues of Warlord Fire, depicted as a barrel-chested giant with billowing hair and wicked amethyst eyes, framed the arch. A phrase in large script, mottled with ash and soot, had been carved into the entryway:

IN THE EYE OF KUNLEO, OLOJARI WILL PROSPER.

Some in the crowd bore picks and iron mallets, others simply lifted bruised and calloused hands, as if in prayer. But all of them swayed, voices lifted in rasping song and jaundiced eyes alight with hunger. From the sidelines, well-dressed bluebloods looked on with nervous scorn. As for the Ember priests of the forge, who stood out in costumes of red and gold, their sympathies appeared to be split. Some acolytes stood with the poor and rioting, joining in their music, and bless

ing them in red clouds of incense. Other acolytes stood with the wealthy, sneering at the rabble, and making signs of the Pelican to ward off evil.

Alarmed at the unrest, our Imperial Guard escort fell in place around us. But barely anyone had noticed our arrival. Instead, the crowd fixated on a wiry man standing above the arch, teetering on a ledge in the mountain. His hair was tied up in a bulky bun, and his face was concealed by a green, scaly mask made of leather trimmed by jagged rows of animal teeth. Wide bands of green leather decorated his chiseled arms.

From the hubbub below, I caught an excitedly whispered name: the Crocodile.

He was beating a talking drum, leading the crowd in song:

My sister’s bones, they have no ears

Ah-ah—but is my sister deaf?

Bones will turn to dust,

But Malaki lives forever.

My mother’s skin is mottled clay,

Ah-ah! But is my mother dead?

Skin may turn to ash,

But Malaki lives forever.

Energy crackled from the ground, rising through my sandals and making the hair on my calves tingle. Perhaps this man was a sorcerer of the Pale Arts: His song was an incantation.

My gaze traveled slowly to the lurid steam rising from the mountain.

Skin may turn to ash,

But Malaki lives forever.

No, I realized with cold dread. Not an incantation: The song was a summoning.

Dayo sensed it the same moment I did. “Stop,” he cried, hailing the man in the mask by waving his arms. “You don’t know what you’re doing!”

The stranger continued to direct his rabble choir, though he cocked his head toward us and seemed to start with surprise. Then his shoulders shook—he was laughing. A chill crept up my spine. I couldn’t shake the feeling that, though Dayo and I had hidden our imperial seal rings, and a long-sleeved linen tunic hid my Redemptor marks . . . this stranger knew exactly who we were.

“He’s doing this on purpose,” I growled.

A crimson glow emanated from the forge’s mouth . . . and then a smoldering hand the size of a boulder punched through the top of the mountain.

She burst forth in a mushrooming cloud of ash and fire sprites: a giant of smooth, obsidian rock. The force blew back my hair, and bluebloods scrambled for cover while all around me, the rabble ululated in rapture. The creature rose until her legs straddled the mountain’s ruined peak, thighs gleaming like marble pillars. Plumes of smoke burst from her scalp, and wings like black sails filled the sky, plunging the day into hazy night. With an agonized roar, the alagbato beheld the forge with bright white coals for eyes.

In that moment, a thought occurred to me and my mouth ran dry:

I may never have seen my father in his truest form.

If he wished to—if my mother had not enslaved him—could Melu of Swana have grown to the size of a mountain? What power had my mother harnessed when she slapped a cuff on that guardian’s arm?

Over the arch, the masked man called the Crocodile crowed with triumph. “She has heard your cries,” he bellowed at the jubilant crowd below. “See what your suffering has wrought! If you cannot profit from the fruits of your labor, no one should! We give their wealth to Malaki!”

“He wants Malaki to destroy the mine,” Dayo said slowly. “But why?”

“I don’t know,” I said through gritted teeth. “But he’s an idiot! If Malaki sets off an explosion, the Crocodile will have a lot more than the mine to answer for. Doesn’t he know volcanoes can explode for miles?”

“Feed their stolen wealth to the flames,” the Crocodile cried, pumping a fist before leaping down into the crowd. “And now we must go. Take your children; go, take cover! Watch from afar as justice takes its course!” But to the man’s apparent chagrin, many of the villagers ignored him. Instead, they turned worshipful eyes to the mountain, numb to the Crocodile’s pleas for their safety.

With a tremor that shook the ground, Malaki spoke:

“IRON. IRON. ALWAYS—THEY DEVOUR. MY HEART—MY HEART—”

She bellowed in a dialect I barely made out—some form of Arit that had died centuries ago. Ash poured from her lips, making the back of my throat smart. Malaki let out a hoarse, thundering cry, as if speaking hurt her.

“SO—MANY—STORIES,” she rasped. “END THEM—END THEM ALL—”

And from the yawning caverns of her eyes, lava flowed in rivulets.

“Run!” I hollered. “She’s going to blow. She’s—” I seized Dayo’s arm and tried to tow him up the path. But he wrenched away.

“Tar.” His dark eyes fixed on Malaki with pity and wonder. “I think . . . I think she’s crying.” And then Dayo—my large-hearted, brave, and utterly stupid better half—threw himself up the side of the mountain.

As I watched in disbelief, he scrambled up the rock face, calling out over the hubbub. “Malaki, what do you want?” His burn scar prickled with sweat. “Tell us. Let us know how to help you!”

“That thing doesn’t need help!” I shrilled, clawing at his tunic to bring him back down. “We do!” But it was too late. The moment Dayo said Malaki’s name, the alagbato paused, turning to stare in wild confusion.

Then a massive hand descended from the sky, blotting out my vision, and snatched up me and Dayo in a swift, bone-crushing fist.

My head snapped back, then forward.

Thérèse’s nausea potion threatened to immediately resurface. I screamed, clinging to Dayo, and in turn he clung to the alagbato’s fingers, trembling . . . but still he met Malaki’s gaze.

“Please,” he said, gagging on smoke as Malaki brought us to her ancient, smoldering face. “We . . . we just want to help.”

Lava continued to stream down Malaki’s cheeks. “ALWAYS—MORE,” she said, in a hot, strangled rasp. “FALLING—HERE. FILL—MOUNTAIN. PAIN—MORE—STORIES.”

For the first time, Malaki’s eyes locked on mine. We both stilled, girl and alagbato, trapped in mutual horror and confusion. I held my breath, preparing for an early journey to the Underworld . . . but just as Kameron predicted . . . a spark of familiarity lit Malaki’s face.

Species smell their own.

“STORIES,” she rasped, though this time her tone sounded focused. Determined. “YOU . . . TAKE THEM.”

Then she raised her other hand, and pressed a massive, rocky finger to my forehead.

Grief, as wide and troubled as the Obasi Ocean, filled every crease of my brain. I cried out, eyes streaming with the tears of peasants. Paupers who descended into the mine before sunrise and emerged with the moon, raking a pittance wage to fill the bellies of infants they rarely saw. I knew the agony of child workers, trapped beneath the collapsed walls of shafts, clumsily erected for the rising profit demands of bluebloods. I groaned through the discontent of scar-handed blacksmiths, fleeced into buying iron of paltry quality, while nobles whisked the best specimens far away to the Imperial Armory.

But the sharpest, most lasting pain was that of the mountain itself. Olojari teemed with generations of tragic memories, stories that had seeped down, down, into the rock, weakening the spirit who lived there. Malaki remembered a time long ago, before Raybearers, before emperors or kings of any kind, when the people ruled themselves, and took little more than what they needed. A time when the stories that trickled down into Malaki’s bones were made of music—the laughter of souls well fed, the beat of picks on stone, bodies lean from strength, not hunger.

Then Malaki lifted her finger. I gasped with relief as the memories subsided, then coughed as Malaki’s smoke filled my lungs. She held me, quiet for now, with an expression on her face like understanding and mild contempt.

“What does she want?” Dayo asked me in a whisper, still gripping the alagbato’s fingers for dear life.

I almost replied that I didn’t know—and then I realized that wasn’t true. The day’s events came together, piece by piece, in my mind, which had always excelled at puzzles. The tapestries surrounding the suite common room. The el

egant noble villas and the ramshackle village. The peasants swaying before the mountain, filthy hands lifted in prayer.

“She wants me to fix it,” I said slowly. “And so I will.” I pressed my hand into Malaki’s giant fingers, sending visions of a hopeful future—of a mountain filled with music. “You won’t have to feel those stories anymore,” I told her. “I promise, Malaki. But if you destroy the mountain now, it will only cause more pain. More—bad stories. So give me time.” I sent her visions of many sunsets, and of moons charting their course across the sky. “More—time.”

Malaki eyed me warily, her grip tightening around me ever so slightly. But right when I thought she would crush us to dust—she heaved a great, ashy sigh.

“LAST CHANCE,” she bellowed, and plunged forward, tossing us back at the foot of the mountain. Dayo and I tumbled to the ground, wheezing and scraping our limbs on the gravel before scrambling to our feet. Then, in a burst of lurid, searing sparks . . . the ancient creature vanished. Malaki disappeared back into the mountain, taking every drop of lava with her.

For now.

Our Guard warrior escort immediately surrounded us, clucking and inspecting us for wounds. They formed a barrier between us and the awestruck peasants, trying to herd us away from the mountain. But I broke their ranks, returning instead to the tall arched entrance of the Holy Olojari Forge. Malaki’s grief had shaken the temple, sending bits of rock, iron, and coal skittering across the clearing. I considered the entrance arch, then snatched a broken lump of coal from the ground.

Dayo looked on in confusion. Tar? His concerned voice blossomed in my head. We should go. In case Malaki changes her mind.

She won’t, I replied. Not if we fix it.

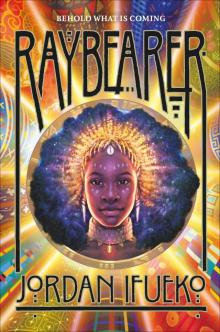

Raybearer

Raybearer Redemptor

Redemptor